Tom Kerr – accelerating the transition

11th October 2010Energy from the land

11th October 2010Viren Doshi – don’t follow the crowd

Viren Doshi cautions Northern Ireland and the Republic against following policy paths set down by others, and finds that small independents often see the opportunity that larger players miss.

Viren Doshi cautions Northern Ireland and the Republic against following policy paths set down by others, and finds that small independents often see the opportunity that larger players miss.

Peter Cheney reports.

Northern Ireland needs to question whether increased competition is good for its energy market as it could cut down on infrastructure investment, according to Viren Doshi. The Booz senior vice-president, who leads the consultancy’s energy practice, told agendaNi that there was an obsession about creating competition and opening up access to pipes.

“All that may make sense in some areas,” he remarked, speaking in a personal capacity, “but for the size and scale you have, you could create a situation where you are so fragmented in a small market that it just becomes uneconomical for anyone to put money on the ground for smart grids, for smart meters or encouraging distributed generation, which is the name of the game of the future.”

He pointed out that many larger regions in Germany, the UK and the USA are dominated by a single player and therefore investment is more coherent.

With over 30 years in energy, Doshi finds he is “still learning each day”. With energy security, cost and climate change trends aligning, he adds: “I find it fascinating. I think this is a time when it’s become very fashionable but I’ve always found it fascinating.”

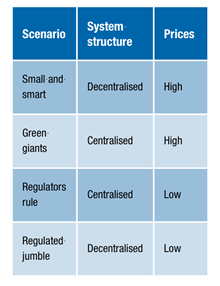

Doshi presented four scenarios for energy systems in 2025 to this year’s Energy Ireland conference:

His starting point is that most European countries have a gap in supply relative to their projected demand. How that gap is bridged depends on the outlook for energy prices and how technology evolves. Tight controls on carbon emissions and a 32 per cent natural gas share are constants in each scenario.

‘Small and smart’ is radically different from today’s situation, with micro-generation and smart grids extensively used. This would see a 42 per cent share for renewables, which replicates the Republic of Ireland’s own target. Electric vehicles and micro-CHP units are commonly used and a complete roll-out for smart meters and the necessary smart grids. Nuclear and coal have small shares, 13 and 12 per cent respectively.

‘Green giants’ is the more centralised alternative to the first scenario. Nuclear power is being extensively developed, accounting for a 29 per cent share, while 23 per cent is generated by coal, principally clean coal using carbon capture and storage. Smart meters are again universal, although there is only limited roll-out for the smart grids.

In the first scenario, individuals and entrepreneurs would have more influence than today. The second foresees the current major energy companies continuing their power in the market. Those giants, he comments, would welcome Ireland shutting down its plants and importing all its energy from Europe as part of a huge grid.

Ireland must consider what is right for its economy: “Quite often it is very easy for Ireland to jump into whatever the Commission or the European Community sets the path for. History has shown that … isn’t always the right answer.”

High carbon prices and fossil fuel shortages make the economics of energy expensive. However, if prices were lower, the economics could be driven by political and regulatory influences. If energy prices were to drop, the ‘regulators rule’ model would achieve the same outcome as ‘green giants’.

High carbon prices and fossil fuel shortages make the economics of energy expensive. However, if prices were lower, the economics could be driven by political and regulatory influences. If energy prices were to drop, the ‘regulators rule’ model would achieve the same outcome as ‘green giants’.

Alternatively, regulation can also produce the fragmented ‘regulated jumble’ model which produces the same outcome as ‘small and smart’.

Doshi still sees merit in coal as an energy source.

“We’ve got to go for the big picture here. Right now, we have a lot of coal. It’s plentiful and available,” he remarks, adding that people got “burnt” in the gas industry. The predicted ‘bubble’ did not happen.

Despite its rapid development, very few new gas plants were switchable between gas and coal. When gas became too expensive, power plants in Asia and the USA had to shut down.

Small players

Some of Doshi’s work has covered the potential for developing tar sands and shale oil as energy sources. Tar sands, in themselves, are not an environmentally sustainable form of energy although he notes they could be made sustainable if converted into gas. Some underground gasification technologies are currently being explored.

Some of Doshi’s work has covered the potential for developing tar sands and shale oil as energy sources. Tar sands, in themselves, are not an environmentally sustainable form of energy although he notes they could be made sustainable if converted into gas. Some underground gasification technologies are currently being explored.

As for shale gas, the technology and effort needed to extract it has to be factored into the carbon cost. There is no shortage of gas pockets, which have been discovered but left alone as extraction was, and is, not commercially viable.

“The moment you find an economic way of getting that out, you unleash a lot of supply of gas on the market.” Healthy gas prices are also needed. $3.50 per million Btu (British thermal units) is marginal but it starts to become viable about $4, and $6.50 would be “very attractive”.

Again, this is a case of the large players not necessarily getting it right.

“In gas as well as oil, we always thought the big companies had the right answer. And guess what? They just ignored the sub-economical small staff. For years, they’ve been going after the giant mega-fields, while the small independents say: ‘Well we can’t afford to go after [that], let’s go and do the best of what we can find.’”

Small independent companies have become highly valued, as seen by Exxon’s $41 billion purchase of XTO Energy this year.

“They thought they knew it all until they realised the little guys had actually got it right.” That example, of small independents changing the game in North American unconventional gas, is also a good analogy for the future of low-carbon power. “Is it going to be the big companies that are going to drive the future or is it going to be the entrepreneurs and the little companies that will find the answer?”

Viren Doshi is Senior Vice President with Booz & Company and leads its global energy and utilities practice. He spent seven years in Exxon, followed by a career in consulting. He holds an MBA from Cranfield School of Management and an honours degree in electronic engineering from Southampton University.