Lessons from the Northern Ireland energy crisis

3rd January 2023

Decarbonisation: The role of energy storage

3rd January 2023The future electricity system

In adopting “technology push” measures to decarbonise electricity, little consideration was given to the system consequences, argues Malcolm Keay, senior research fellow, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Keay believes that governments, businesses, and analysts need to learn from mistakes in the decarbonisation of electricity and adopt a systems approach to the wider decarbonisation of energy.

Stressing that there will be no return to the electricity system, or indeed, energy system of the past post-pandemic, the energy policy expert believes in the need for fundamental changes to how the electricity system is planned, analysed, and operated if decarbonisation ambitions are to be reached.

To date, electricity has been the key focus for decarbonisation in Great Britain, highlighted by a plummet in emissions since 2010 which have seen electricity emission reductions form over three-quarters of total emission reduction.

Keay highlights that the emergence of low-carbon solution technology, alongside no requirement for operational change on the part of the consumer, have made the electricity decarbonisation politically easy but stresses a much greater complexity exists in the process.

“The outcome is that electricity as a system is changing rapidly, for example, the cost structure was once mainly marginal costs, but the future system will be mainly capital costs. Logically, pricing should change too because pricing in a short-run marginal cost basis doesn’t make sense when you have an industry that does not have short-run marginal costs. This has not been fully recognised and I believe will come back to bite us over time,” he states.

Another example of change outlined by Keay, which he believes has yet to be fully appreciated is the structural change to generation moving from a centralised system to a decentralised one. “In the UK, renewables have been multiplied 15-fold since 2000 but decentralised generation has multiplied 1,000-fold, meaning we are getting a very differently structured industry. How we think about industry must change.”

The Senior Research Fellow believes that a theoretical appreciation of change exists but believes little recognition has been given to the potential implications. Highlighting that, at present, governments drive virtually all investment and that even in relation to operation, prioritisation of renewables means little influence by markets, Keay believes that “electricity markets are broken”.

Similarly, he believes that regulation is effectively broken, pointing out that the four traditional elements of regulation (two competitive and two monopoly), neglect an emerged fifth element: consumers and prosumers.

“The distinction between the monopoly and non-monopoly elements is fading,” states Keay. “We have seen, for instance, in the UK capacity market, the interconnector has been competing with generation and you have a network asset competing with generation assets.”

“In the UK, renewables have been multiplied 15-fold since 2000 but decentralised generation has multiplied 1,000-fold, meaning we are getting a very differently structured industry. How we think about industry must change.” Malcom Keay, Senior research fellow, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

Policy

Emphasising that overall policy is lagging behind events, Keay says that piecemeal interventions, for example, a focus on offshore wind, fail to address the need for whole system optimisation.

To some degree, the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 provided a glimpse of the future energy system. Changed work and travel system meant that in Great Britain, generation from renewables exceeded that from fossil fuels for the first time, while the carbon intensity of generation dropped 95 per cent below 1990 levels and decentralised generation rose to over 30 per cent at times.

The pandemic accelerated some trends that were predicted to happen on a longer timescale, meaning that some outcomes were foreseeable, however, as Keay explains, not all change has taken place as previously expected. For example, balancing cost as a share of generation cost increased, as expected, but unexpectedly, large discontinuity was seen in relation to price. The balancing price as a share of total generation cost in Great Britain went up from 5 per cent to 25 per cent in 2020.

“This discontinuity has two possible consequences,” explains Keay. “Firstly, that fairly low-level problems can suddenly jump up and bite when you are not prepared for them and secondly, that the validity of pricing is further undermined. The increased costs have to be borne somehow and along with many other costs, such as renewable support, are smeared across the price. So, the prices are increasingly not having much of a function in demonstrating cost, instead they are simply a mechanism for cost recovery.”

Other unexpected outcomes during 2020/21 highlighted by Keay is that the misconception that nuclear is needed as baseload generation was somewhat disproven as the grid paid nuclear plants to turn off when there was excess generation. Additionally, he says that in the demand side, placing energy efficiency at the centre of policy is “simply wrong”. “When you have a situation where you have 40 per cent of wind power being dispatched down, energy efficiency is not what you need, you need a better system with demand side flexibility,” he says. “Energy efficiency may have a part to play in demand side policy but to emphasise it as the centre of policy is wrong and risky in terms of the future ability of the system to cope. Emphasis on energy efficiency is not going to deliver the new system which is needed.”

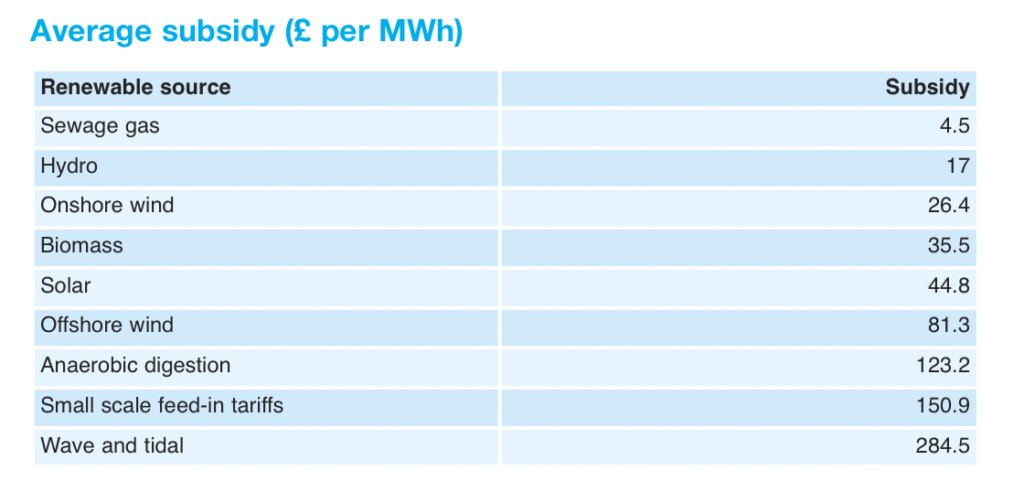

The UK’s National Infrastructure Commission estimates that system optimisation could be worth £8 billion annually and Keay highlights that with growing intermittency in the system, a range of options for balancing exist. However, he states that different price and regulation regimes of these options are problematic.

“As long as you have a position where the prices in one area are set in a different way from prices in a different area, it is impossible to see how the market is going to sort this out. However, there is no overall system planner. There is no one else sorting it out, so it is just not clear how we will get to an optimised solution.”

Keay explains that the impact of the lack of coherency spreads beyond electricity and into other spheres of the energy market. Highlighting the absence of a systematic overall approach to getting the right balance on price between sectors, he points to a current tax regime which potentially makes electricity more expensive than other fuels, due to bearing internal costs, which will act to discourage its use in heating and transport.

Although the UK Treasury has acknowledged that some of the tax costs currently being borne by electricity need to be shifted to gas, politically, no direct action has been taken.

Keay believes that a systems approach could reduce the cost of electricity through greater efficiency and the Carbon Trust estimate a £16 billion per year saving if such an approach was adopted.

“At present, one of the major problems with electricity is the average load factor being well under 50 per cent. By 2030, 40 per cent of wind power would be dispatched down and that is a very inefficient way to run a system. What you have to do is think of the energy system as a whole and ways in which electricity could be used across that system. That is not the current approach of the government, who are pursuing a piecemeal technology push approach, with various projects coming to fruition at various times and in various ways. 2050 may seem like a long time away but big decisions in relation to networks, hydrogen etc are needed now to get the right mix in each network.”

As Keay highlights, the issue is not just prevalent in the UK. In Ireland, for instance, dispatch down of wind power was in the past relatively minor at around 4 per cent but by 2020 it rose to about 14 per cent. EirGrid predicts that by 2030, this could rise to 40 per cent. “The system consequences need to be thought through properly,” he states.

Keay assesses that even with technical solutions, the political task of developing networks in an efficient manner and under a presumably liberalised market approach in the timeframe will be challenging. “The fact is that all the networks we have now were developed under a monopoly approach in one way or another and governments had not really thought about how they would develop these new networks and how they would get them in the right place at the right time under a liberalised system.”

Summarising, Keay says that it is clear that governments and most key stakeholders did not pay enough attention to the systems issues in decarbonising electricity and are still trying to pick up the pieces as a result. Given that systems issues will be even more fundamental in the next stages of decarbonisation, governments and stakeholders need to start thinking in systems terms.