Addressing the cyber threat to electricity networks

25th November 2019

The future role for storage in Ireland’s electricity and heating sectors

25th November 2019Let’s start acting like it’s an emergency

It might seem like a long way to 2030, writes David Connolly, CEO of the Irish Wind Energy Association, but whether we hit our Climate Action Plan targets will largely be decided in the next couple of years.

In October 2018 the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) told us we had 12 years to keep global heating to a maximum of 1.5°C. Beyond that, the lives of hundreds of millions of people will be vulnerable to drought, floods and extreme heat. Many will be forced to leave their homes as refugees.

Today, we have 11 years left and though the Dáil declared a climate and biodiversity emergency in May it is still difficult to detect the sense of urgency, the commitment to do whatever it takes to halve our CO2 emissions by 2030.

The Climate Action Plan produced in June is a significant step in the right direction but an emergency isn’t really an emergency until we start acting like it is, until we start finding solutions to some of the key questions we need to answer if we are to hit our 2030 targets.

How can we get the growing pipeline of wind and solar projects through the planning process more quickly? How can we enable renewable energy projects to connect to the grid more swiftly? And how do we strengthen that grid to ensure the power produced by renewable energy gets to where it is needed? Reform of our approach to planning energy infrastructure is central to all of this.

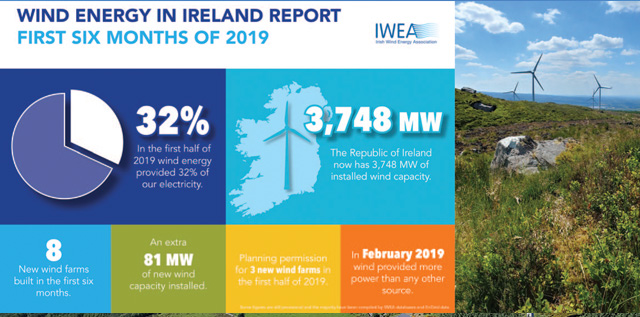

Over the last two decades, wind energy has evolved from a near-negligible presence in Ireland’s electricity mix to providing almost a third of Ireland’s electricity – far more than coal and peat combined – and steadily narrowing the gap on natural gas.

It is a huge accomplishment and our industry can be proud of what it accomplished with the help of a supportive government policy framework and a constantly improving technology which has driven the price of wind energy down again and again. Today, we face an even greater challenge: to hit the 2030 target of 70 per cent renewable electricity we need to double the amount of renewables in the electricity mix in a decade — half the time it took us to build our industry.

Planning reform

However, we have a planning process for the development of renewable energy that is cumbersome, contradictory and confused. We need one that is fair and transparent. Everyone affected by a project has the right to be heard and, if they feel their concerns have not been taken on board, to object. This right must be protected, but we also need a planning system that deals with applications more quickly and that fast-tracks critical infrastructure like renewable energy projects and grid reinforcements.

Vexatious objections must be tackled and the judicial review process streamlined. This is not about giving anyone a blank cheque. Developers should always be held to account. Our members must continually improve how we engage with communities and ensure our planning applications are robust and evidence based. No developer can be allowed to ignore legitimate local concerns.

Nor, at the same time, can the development of renewable energy be delayed or prevented by those who are opposed to action on climate change, or by what Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government Eoghan Murphy TD rightly calls Ireland’s “objection culture”.

One of the key challenges for wind farm developers are the timelines for planning decisions to be made. An analysis of wind farm appeals decided by An Bord Pleanála between 2017 and mid-2019 found that, on average, appeals were under consideration for 66 weeks. This is far in excess of An Bord Pleanála’s 18-week target and three times the average period for all appeals decided in 2018.

Instead of 18 weeks being a target, it should be a statutory decision period and An Bord Pleanála should be given the resources to ensure it can deliver — just as it has met statutory decision periods for strategic housing developments.

In addition, while the setting up of a specific unit within An Bord Pleanála to handle Strategic Infrastructure Developments (SIDs) is welcome, I believe they can go further by having a dedicated team for renewable energy projects capable of handling wind, solar, grid and storage projects.

High Court

The challenge for those of us working towards the 2030 targets has been exacerbated by two recent High Court judgements. First, the O’Grianna judgement determined that a wind farm’s grid connection requires an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). This was followed by the Daly decision which found that projects requiring an EIA must obtain planning permission and — therefore — the consent of landowners to lay underground grid connections.

Combined, these two judgements will severely slow down, even prevent, any linear development — not just wind farm connections — along public roads. By amending the Planning and Development Regulations 2001, Minister Murphy can remove the requirement for landowner consent for planning applications for utility services along public roads. Doing this would help eliminate a significant roadblock standing in the way of getting to our 2030 targets.

Perhaps most important of all, we need the new Wind Energy Guidelines — due to be finalised before the end of the year — to strike the proper balance between Ireland’s need to develop renewable electricity and the concerns some individuals and communities may have around wind farm development.

The new guidelines must be based on evidence. They must rest on a robust scientific analysis. They must draw on proven expertise — national and international — in noise assessments. Only by doing this can Minister Murphy develop a set of guidelines that will ensure the continued development of a thriving wind energy industry, steady progress in cutting our CO2 emissions and reductions in the price of electricity.

Referring to the 2030 targets at the launch of their new strategy in September, EirGrid CEO Mark Foley told the audience that the question of whether we would achieve the 2030 targets would be “decided in the first half”. By the middle of the next decade we will know what projects — wind, onshore and offshore, solar and storage — have managed to successful navigate their way through the labyrinth of the Irish planning system.

Any project not through planning by 2025 is unlikely to make much of a contribution to our 2030 targets and every project lost means more CO2 emissions. That is why the next two years are so crucial. It is now that the Government — and all parties in the Oireachtas — need to work together to reform our planning system.

We are living in a climate emergency. Let’s start acting like it.

E: david@iwea.com

W: www.iwea.com