CASE: Helping put Northern Ireland’s sustainable energy sector on the map

10th November 2017

Why corporates will accelerate transition to renewables

10th November 2017Ireland’s ambition:What should our renewable energy targets be for 2030?

Bord na Móna hosted a round table discussion at its Mount Lucas wind farm facilities in County Offaly on renewable electricity’s role in decarbonising the Irish economy.

How significant will the role of electrification be in the decarbonisation of the Irish economy and in what sectors will electricity play a role?

Oisín Coghlan

The more research we have in Ireland, it is becoming clearer that the fastest way to decarbonise is to electrify as much as possible because decarbonising the electricity system is the clearest thing to do. Electricity will also play a key role in Ireland’s transport and home heating. It will be essential in our journey to decarbonise the economy over the coming decades.

Oisin Coghlan

John Reilly

We have the tools to do it and we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Looking at what is happening globally with the electrification of vehicles it doesn’t really matter what policy-makers or the public do, the fact is that the car manufacturers have shifted into manufacturing electric vehicles and that tells us which way this is going. One key aspect is that the benefit of decarbonisation will not happen using electricity as a vector if we stop the progress of RES-E [Renewable Energy Support for Electricity]. That needs to continue. There might be a sense that we will have achieved significant penetration of renewables onto the electricity system by 2020. If we relax and stop then that will not feed through to the wider decarbonisation of the economy.

Laura Burke

The electricity sector accounts for 19 per cent of [greenhouse gas] emissions in Ireland. Therefore, it needs to play a major part in reducing our emissions. Unlike the other sectors the technology is there in electricity; we can see it outside. There is also the potential to electrify other sectors; transport and heating but there is no point electrifying these sectors if the electricity is generated using fossil fuels.

Owen Wilson

The electricity sector is required to decarbonise by 2045. Working back from there, what are the zero carbon energy sources that are going to be available? And what is the possibility of developing those? And what infrastructure will be required to deliver them? How much of that is already in place and ultimately, what is the cost? There are other forms of energy that have potentially significant roles to play. For example, in transport if we electrified all the cars that would be less than half the transport fleet. For HGVs, shipping and airlines other fuels will have to be used. Other technologies will include hydrogen, biogas and biomass. Electricity has the huge advantage in that the infrastructure is largely already in place. It may have a dominant role but it will not be the only source of low carbon energy.

Jim Gannon

In both the heating and transport sectors, we can already see that the early movement is by consumers. In the residential sector, we see consumers beginning to install heat pumps or more sophisticated storage type heaters. Similarly, in the transport sector, although market penetration is low to date, the consumer is increasingly choosing to purchase hybrid and fully electric vehicles. But we need to make this transition in a mature way. There is little point in electrifying energy services, if we continue to use these services in an inefficient way so, for example, we should continue to make our building stock more efficient alongside electrification. Furthermore, there is also little point electrifying heat and transport of we do this in the absence of decarbonising that electricity.

Tom Shanahan

Electrification has a very significant role to play in decarbonising the economy. The fact that electricity is already being generated on a carbon neutral basis gives a huge potential that we need to exploit. The degree to which we electrify transport, road and rail, will have a major impact – although there are still some technical issues to be resolved. The electrification of transport could be greatly enhanced by other policies such as planning. Where we live and work has a huge impact. The NPF [National Planning Framework] looks to consolidate development and tries to reverse the trend towards long commutes. Yes, electrification is important but there are a lot of other factors such as planning that will also be important.

The recent RESS consultation suggests a RES-E level of 40 per cent by 2030. What level of RES-E ambition should Ireland have in the context of the evolving EU Framework to 2030 and the higher ambitions by 2050 and why?

Laura Burke

In Ireland, we have tended to focus on EU requirements. We should step back and look at the National Policy Position, which is an 80 per cent reduction in emissions across the electricity generation, built environment, and transport sectors by 2050.

Laura Burke

Reliance solely on the ETS [emissions trading scheme] to push electricity towards renewables is a mistake. It should be an element but we can’t rely on just that. The price of carbon is low at €7 per tonne in the ETS and the emissions intensity of power generation has actually increased over the last two years. As energy demand increases we need to strive to do more and more renewables.

There are also wins in terms of health. Moving away from fossil fuels, whether for power generation or transport, there are opportunities to use cleaner fuels which will have an immediate effect on people’s health and well-being.

The ambition should be at least 80 per cent renewables by 2050 but the longer we leave it, the more expensive it will be and the more we will have to do in a shorter period of time.

John Reilly

The other benefit is security of supply, as most renewable energy tends to be indigenous. That is not always recognised in any cost benefit analysis of renewable technologies. In 2017, around 20 per cent of electricity generation will come from coal and peat. With the new ETS price the market will remove this and the PSO finishes in 2019. The key question is what will replace that 20 per cent? The most obvious answer is natural gas. Although cleaner, it is a fossil fuel. The 20 per cent equates to 35 TWh and renewables are unlikely to replace such a big chunk given the community acceptance issues at present. That will mean 65 per cent of power generation in 2030 will be from gas.

Jim Gannon

Directly relating to the RESS, Ireland has to achieve, as a minimum, its fair contribution to a European target. However, Ireland may also have ambition to set conditions that may enable us to perform better than that. There is clear signalling of this in the new RESS consultation, which admittedly takes 40 per cent as a reference case but also increased levels of renewable deployment beyond 40 per cent and looks at the costs and challenges associated with that.

Oisín Coghlan

In a 2050 context, the Energy White Paper states 80 to 95 per cent as an explicit target for Ireland. It is therefore disappointing that the proposed target for 2030 is 40 per cent which is the same target for 2020. I know it will be of a larger demand but it is not good enough. A trajectory of 40, 40, 90 doesn’t make sense. Setting proper targets induces action.

Owen Wilson

There is a fundamental philosophical issue in that Europe established the ETS as a tool for the electricity market to deliver decarbonisation at the least cost and, in the 2030 package, it now appears to have abandoned that approach in favour of prioritising command and control instruments. This appears to reflect a return to the historic approach of the EU to addressing environmental issues and, to some extent perhaps, inter-agency rivalry. Applying both types of instruments adds costs for businesses and consumers for limited or no environmental benefit. If this view reflects the real situation then a more ambitious approach to target setting can be considered.

Tom Shanahan

On the level of ambition, we should have high targets. The issue of security of supply is crucial as we are a small open economy and increasing the level of renewables will go a long way to mitigating that vulnerability.

In the wider context, renewables will enhance ‘brand Ireland’. A lot of international companies are interested in having a sustainable energy supply and more renewables will therefore help attract FDI. The level of ambition, not withstanding the challenges, should be high as it will give a certain momentum to decarbonise the economy. Technology will continue to improve over the period to 2050 and that will help pick up the pace of change.

What are the key barriers to achieving this level of RES-E penetration on the electric power system by 2030? And how do we remove these barriers and minimise the risk to achieving this 2030 ambition?

Owen Wilson

Market design is the primary barrier if we are to continue with the market-based approach to the delivery of electricity services. Even the primary goal of the RESS consultation is to minimise the cost of schemes, but there isn’t a cost of support schemes there is just the electricity cost. We shouldn’t even be calling it a support scheme – it is the underlying cost of delivering electricity to consumers. If the market can’t encourage that type of low carbon investment then the transition to a low carbon electricity system will simply not happen. As it is today, the market cannot do that with an energy-only type of market. It is not capable of doing it. Therefore, we have to start with the design of the market.

Owen Wilson

John Reilly

We have a market now across Europe where the vast majority of investment is from the private sector. The hardest part of delivering that investment is sitting in front of the bankers and convincing them they will get a return from the project. You can have all the ambition you want, but if people like me can’t present coherent business cases to build more wind farms or to put storage on the system nothing will be achieved. I have just visited a 50MW wind farm in Warwickshire, UK with battery storage, because the UK specifically is making provision for battery storage services as part of the bolt on to its market. We are not doing anything like that. We have a tiny pot for ancillary services and we are cutting capacity payments. We are going to have a real challenge on this island keeping the lights on during the period 2025 to 2030.

During the economic downturn the energy sector was the only sector building infrastructure because we had to decarbonise. Now the economy is picking up other sectors are now looking to invest in infrastructure again. The public acceptability of any form of infrastructure, not just energy, is a problem and renewable electricity may cost more than it should do because of the lack of public acceptance.

Oisín Coghlan

We have had a perfect storm regarding public acceptance. There are some parallel experiences between Irish Water and wind energy. One common factor was the context of austerity and recession. Irish people felt hard done by. In both cases people thought we couldn’t stop Anglo Irish or the Troika but they could stop that wind farm there or that water meter in front of them. It was associated with external forces doing something to ‘my community’. That has left us with a challenging legacy but if we have a five to eight year period of economic growth some of that might fall away. That doesn’t take away the need for engagement by companies with communities. That’s not principally about megawatts but more about ‘hearts and minds’ or democracy and participation. People do feel put upon and we have to find the right way to engage with that or we will not get any of this done. Small scale solar generation will open the possibility for households and small businesses to do their own generation and this will help reset this debate and move on. Shared ownership will also help and that has been the experience elsewhere in the world.

Jim Gannon

Community involvement in energy projects is a fundamental part of the new RESS, and draws significantly from international best practice. However, the communities themselves will be the ultimate arbiters of to what extent they become involved. Experience in other jurisdictions shows that despite the fact that you can offer a certain quantum of development opportunities to communities, they often don’t take that up to the maximum. However, offering the opportunity has a value in itself.

Oisín Coghlan

That must be done in good faith and with the proper supports. Particularly with the legacy it will be portrayed as a sham.

Laura Burke

Overall, we tend to be good at writing high-level plans but not so good at translating them into reality. You can’t just set the ambition high without some sense as to how you are going to do it. We have a policy position on climate change and we have an Energy White Paper. But how have these been translated into actions? We also have perverse incentives. We talk about decarbonising public transport but we are still buying diesel buses. We say we should decarbonise the electricity system but we are still burning coal and peat. In fact, currently the PSO levy in Ireland for peat is four times that for renewables per MW generation capacity supported. We need to see good concrete actions to show that government means business and so that people can buy into it.

On societal acceptance, as a regulatory authority we see this every day of the week. People don’t want something imposed on them. They want to be heard and engaged with. Telling a community that we are going to do this is not engagement.

John Reilly

Ultimately, the engagement is through the planning process. The planning process in Ireland allows a lot of engagement. We engage with communities on the form and nature of the development and we will discuss with them things that we can change and to listen to their concerns. Where we can change things, we will. The ultimate arbitration of this is the planning process.

Owen Wilson

The mediator between overall national objectives and individuals at a local level – in some cases they say I just don’t want this development – is the planning process. We have a major problem as there is no longer the same level of trust in that system. That certainly has been the experience with the North South Interconnector. This is an institutional problem rather than just a political leadership problem.

There are other barriers. On a GDP per capita basis we are the second wealthiest country in Europe and the fifth wealthiest in the world and if we can’t afford to reach our targets then no one can. When it comes down to it we still want ambitious targets and yet every time there is an electricity price increase there is an outcry. We need a mature discussion to resolve the affordability issue.

Tom Shanahan

The scale of what we have to deliver is challenging but there is a lack of policy guidance on many aspects of it. We do have guidance on wind but there is nothing for solar or biomass. These policies are important for planning authorities to give them some sort of reference framework for their decisions.

Tom Shanahan

Jim Gannon

Political leadership is essential but we must also work with the media to show examples of good practice. If the media reported proportionately the views of people on the ground, this would more naturally be channelled to our constituent politicians and that would influence things for the better. The media has a powerful role to play in reporting some of these discussions and the headlines tend towards the sensationalist and the negative.

Laura Burke

We need to be careful when we criticise the media. It is a very big group and in our experience in the EPA we have dealt with progressive and interested media who are reporting this issue in a very responsible and considered way.

The Citizens’ Assembly on climate change has been really powerful and has had over 1,200 submissions. There was an incredibly rich, thoughtful debate and having participated in it myself I was taken by the level of engagement and the knowledge. Hopefully that level of interest will transfer into the broader political system.

What approach to you think the Government will adopt to the required Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP)? Where will the balance of focus be in terms of contributing to European-wide RES and GHG targets, while reducing emissions domestically?

Jim Gannon

The NECP will for the first time require us to deliver a high degree of specificity around our 2030 targets. It requires not just an end goal to be reached but a timeline of performance that will be reviewed at two-yearly intervals. There will be a great degree of detail delivered within it in terms of the instruments that will be applied and how that breaks down into each of the sectors. There will be significant focus on it from Europe and they will be able to influence and advise on how we implement that.

Jim Gannon

Laura Burke

Although the EPA is not central to the plan, part of it will streamline existing reporting. We currently have the role, and will continue to have the role, in GHG emissions inventory and projections reporting. There is an opportunity to pull together the whole system with one plan. I chair the management board of the European Environment Agency and it was interesting to see DG CLIMA, DG Environment and the EEA looking at that reporting and how the overall Energy Union governance will be managed. It is not all new and it will be really important to do a Strategic Environmental Assessment on the plan, otherwise it will be disconnected with the reality on the ground.

John Reilly

The National Energy and Climate plan will effectively dictate energy policy in Ireland for the period from 2020 to 2030. If we are to be successful we need to engage with society so that everyone understands that this is where we are going in terms of energy policy and there is a real reason why we are doing this. One issue is the different forms of technology. There is a clear signal in the RESS consultation that this renewables plan needs to be the lowest cost it can be, using least cost technology auctions. There will only be one winner in that: onshore wind. Our sense in Bord na Móna is that this approach is being taken to keep the PSO cost down. Politicians and policy-makers are most concerned at the moment about the cost of decarbonisation. You cannot decarbonise an economy without investment and increasing costs but what you hope is that you arrive at a point that energy costs are lower than they would have been otherwise. How we fund the transition to a low carbon economy is important. Whilst Bord na Móna has been very appreciative of the PSO which was put in place to support employment. The one thing we need to ensure we don’t do in the context of energy policy is conflate energy policy with employment policy. The PSO is supporting an element of security of supply as peat is an indigenous fuel but that policy decision taken 15 years ago was about protecting employment in the midlands. If we are going to do this properly, in a way that will hopefully maximise employment, don’t have employment as a central part of it.

Oisín Coghlan

I agree that policy is sub-optimal and it is an expensive way to support employment. We need to look at a just transition and to get the architecture right. If you look at how we act as a state when a US multinational pulls out; overnight all the agencies come together and put in place a plan. We need to do that now for the Midlands in a positive way – and now, rather than pretending nothing is going to change.

What one area should senior managers and policy makers focus on to help deliver Ireland’s renewable energy ambitions?

Oisín Coghlan

There is no silver bullet but one thing that would broaden things out is small scale solar. If it isn’t supported in the RESS then it should have a parallel scheme. We would put a cap on it at €14 million and would look to put solar panels on every school.

John Reilly

Leadership. If we, whether semi-state or private developers, are delivering projects to achieve national policy objectives we then need everyone to understand why we are doing this. The industry has an obvious role in that but the general public is sceptical as to what industry says. Therefore, we need political leadership at a national level. I’m hoping the National Energy and Climate plan will do that; to explain to the public why it is necessary to do this.

John Reilly

Laura Burke

An explicit focus on the national policy position and how that is transferred into action. As part of that we need a carbon price floor to incentivise action and an explicit move away from coal.

Owen Wilson

The early flagging of a prohibition on fossil fuelled transportation and a similar prohibition on non-networked fossil fuelled heating systems.

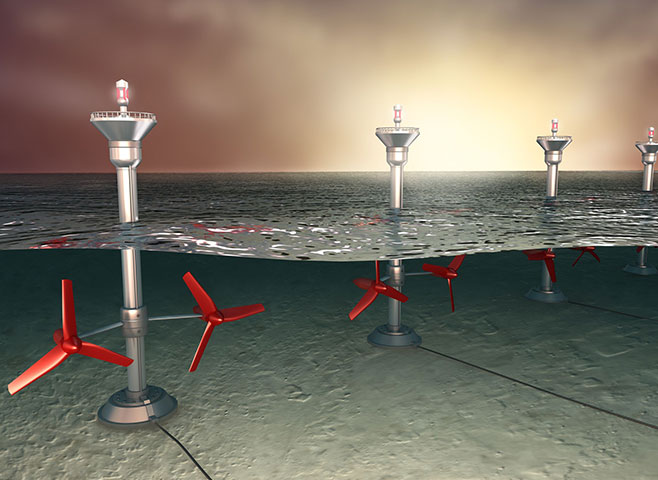

Jim Gannon

Critical to all of our actions will be a planning and consenting process that truly delivers. One with a reasonable timeline and certainty for developers and financiers, but which is also trusted by key stakeholders and communities. Recent examples of many planning and consenting processes across a range of industries underlines that further work is needed here. If we get something that works, both onshore and in the marine environment, it will help catalyse activity and promote investment.

Tom Shanahan

Leadership and policy are key. We need a high level of ambition. Land use policy +-*is crucial and we need an overall SEA [Strategic Environmental Assessment] as we don’t want any conflict, with good quality agricultural land being used for other uses.

Laura Burke

Laura Burke was appointed by the Minister for the Environment as Director General of the Environmental Protection Agency in November 2011 and served as a Director within the EPA since 2004. Laura is the Chair of the European Environment Agency (EEA) Management Board and is also the Chair to the Societal Challenge 5 Advisory Group for Horizon 2020. Prior to joining the EPA, she worked in the private sector. Laura is a graduate chemical engineer of University College Dublin (UCD), holds an MSc from Trinity College, Dublin and is a Chartered Director. In 2016 Laura was awarded the UCD Engineering Graduates Association (EGA) Distinguished Graduate Award.

Oisín Coghlan

Oisín Coghlan has been Director of Friends of the Earth Ireland since 2005, the Irish member of the world’s largest grassroots environmental network with over two million supporters in 75 countries. Oisín is on the steering committee of the Environmental Pillar, the advocacy coalition of national environmental NGOs, and sits on the National Economic and Social Council (NESC). Before joining Friends of the Earth, Oisín worked for 10 years in the areas of overseas aid and human rights.

Jim Gannon

Jim Gannon is CEO of the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland since May of 2016. He has worked within the energy sector throughout his career, delivering projects at a European, national and regional level for public and private sector organisations. This has included both policy and infrastructure projects. He is an Engineering Graduate of NUI Galway, with a Masters in Environmental Assessment and an MBA from the UCD Smurfit School of Business. Jim also serves as a member of the national Climate Change Advisory Council.

John Reilly

John Reilly is a member of Bord na Móna’s senior executive team with specific responsibility for the PowerGen Business Unit. He is responsible for the strategic development, construction and commissioning of the pipeline of projects in the development portfolio. John has over 15 years’ experience in the energy sector and was previously part of the senior management team at Edenderry Power. John has worked for a number of major international utility players in the sector, such as the German utility E.ON and Fortum, a Finnish utility company. John is on the Board of the Electricity Association of Ireland, is vice-Chair of Ibec’s Enegy Policy Commmittee and holds a PhD in Chemistry from UCD.

Tom Shanahan

Tom Shanahan C. Eng. FIEI is currently Acting Director of Services in Offaly County Council with responsibility for Housing, Planning, and Birr Municipal District. He has held a variety of engineering roles across Roads, Water Services and Environment with Offaly County Council since 2000.

Owen Wilson

Owen Wilson is Chief Executive of the Electricity Association of Ireland, the representative body for the industry on the island. He was previously employed at ESB where he headed the Group Health, Safety and Environment function. Owen is a former chair of the Environment and Sustainable Development Policy Committee of Eurelectric, the European electricity industry association, and a member of its Executive Committee. He has worked closely with industry, NGOs and officials on a range of national and EU energy, climate and environmental policy issues.