DP Energy: A world fully powered by renewable energy

12th October 2022

Ireland’s leading renewable energy company planning three Irish offshore wind projects

12th October 2022Developing Ireland’s hydrogen opportunity

University of Galway’s Rory Monaghan assesses where hydrogen fits in Ireland’s future energy system.

Monaghan believes that an opportunity now exists for Ireland to seize on hydrogen production and deployment. Ireland faces a challenge in meeting its 2030 decarbonisation goals, but an even greater challenge exists beyond 2030 in reaching the hard-to-abate sectors.

The academic is adamant that hydrogen has a key role to play in tackling these hard-to-reach sectors but stresses that it should not be viewed as a solution in isolation.

Pointing to high volumes of lost energy included in final energy consumption figures, he says: “Hydrogen has a role but upfront energy efficiency and demand management should be our number one priority. Also important is changing societal behaviours, moving towards more efficient uses of energy, and incentivising those right decisions.

“We should be electrifying as much as we can, as fast as we can,” he adds.

Monaghan is buoyed by the fact that Ireland has a track record as a world leader in the delivery of renewable electricity, a strength that will be tested as the transition fosters greater demand for renewable electricity. An estimated 75GW of offshore potential underpins Ireland’s potential capacity for delivery, however there is also an evident need to decarbonise those areas for which electrification will not suffice, which Monaghan describes as “high mileage things, heavy things, hot things and hard-to-make things”.

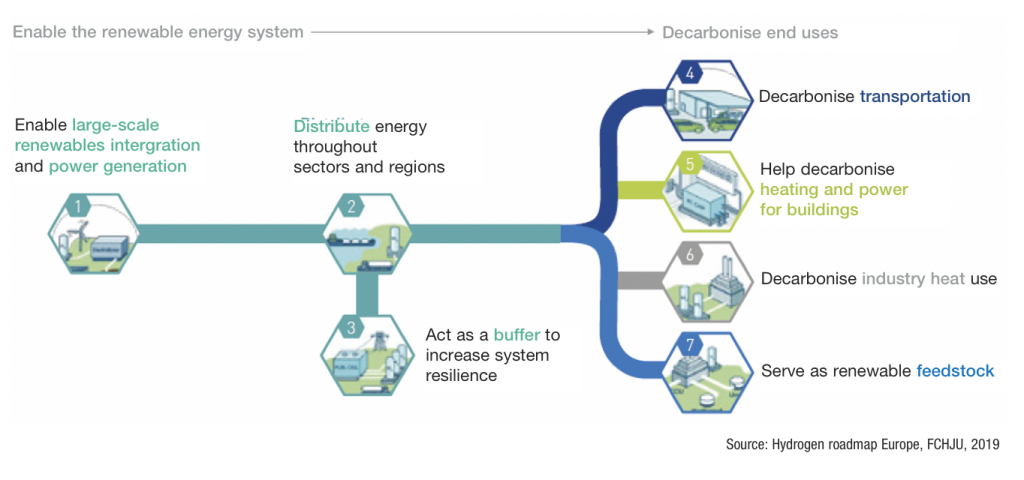

“Our heavy-duty transport, our industries and our things that need to move long distances [i.e., ships and aircraft etc], will be very hard to electrify. We also have the challenge that a variable renewable system opens up. Hydrogen is potentially a missing link that can help us decarbonise those hard to abate sectors, help us store energy for long periods of time and move energy over long distances,” he explains.

Monaghan and his team have been developing a theoretical map for the potential end service use of hydrogen in the Irish economy in the short, medium, and long term.

Short term

Setting out the immediate opportunities, Monaghan says that curtailed wind is a resource which should be utilised but the academic recognises that temporal availability makes it unlikely to feature largely in the long term.

Tanker trucks and gas grid blending represent current opportunities in relation to distribution and storage, while end uses already exist in the form of some buses, trucks and, again, gas peaking plants. “We have hydrogen value chains available to us in Ireland currently,” explains Monaghan.

Medium term

Looking to the medium term, Monaghan says that plans to produce hydrogen from dedicated renewable generators will allow for more constant, larger scale production of hydrogen. This in turn enables the de-risking of projects, the inclusion of more off-takers and potentially larger scale storage using the gas grid.

Potential end uses again included the likes of coaches, trucks and trains but expand beyond gas peaking plants to combined cycle power plants. Industrial heat, data centres, and export also come into the equation.

Monaghan explains that he used to consider the potential for hydrogen in a more long-term (post-2030) scenario but has readjusted his thinking on the basis of Germany appointing a dedicated hydrogen commissioner to travel the world and sign supply agreements on the back of its commitment to a hydrogen future and the absence of levels of production it requires.

“We need to identify the synergies that do and can exist between renewable electricity supply, electrification, and hydrogen.”

Rory Monaghan

Long term

Monaghan’s longer-term outlook for green hydrogen production in Ireland includes those hardest-to-abate sectors including shipping and aviation, but the academic warns: “We have to be open to the fact that perhaps not even hydrogen would be the suitable decarbonisation fuel. Perhaps we need to use hydrogen as a building block to make something else – a synthetic, totally renewable version of shipping or aviation fuel.”

He adds: “It is also worth recognising the potential of hydrogen in the longer term to stimulate new industries that we have yet to imagine or resuscitate some old ones. Associated to that is the creation of jobs, the building of energy security and the appeal of FDI into the country.”

Action

Highlighting a range of projects which are already under development across the island, the most advanced of which is a collaboration between GenComm, Energia, and Translink in the North which unveiled a fleet of hydrogen buses in March 2022 through electrolysis, Monaghan explains that all projects share common risks. While some of these risks, including planning, permitting, supply chains, and skills are not unique to hydrogen projects, a central concern seen amongst developers is uncertainty around how hydrogen is going to be treated in Irish energy policy.

In July 2022, the Department of Environment, Climate and Communications (DECC) launched a consultation on developing a hydrogen strategy for Ireland. Ireland lags behind some 20 countries who already have national

hydrogen strategies (although not all of these target green hydrogen) and Monaghan has called for a future strategy to be “ambitious, evidence-based, targeted, and coherent”, adding that it should be quantitative to give certainty.

On ambition, Monaghan highlights that the Climate Action Plan foresees a role for renewable gases (including green hydrogen) of 1-3 TWh by 2030, one of the lowest ambitions of any of the countries who have published a national hydrogen strategy to date. Posing the question of how much ambition Ireland can afford beyond 2030, Monaghan stresses that hydrogen production is dependent on how much renewable electricity generation can be built.

Taking 35GW (half of Ireland’s upper limit offshore wind potential) as an example, Monaghan estimates that Irish green hydrogen could have capacity to meet 20 per cent of EU aviation demand or over 25 per cent of EU shipping fuel demand.

While countries like Australia and Chile will benefit from combining wind and solar resources to produce the cheapest hydrogen, Monaghan estimates that, given its renewable electricity potential, Ireland could be one of the cheapest hydrogen producers in Europe.

On the need for an evidence-based strategy, Monaghan emphasises that any outlook must focus on the net zero by 2050 target, rather than the 51 per cent production by 2030 one because it is unlikely that hydrogen will have a major decarbonisation impact until post-2030.

“Identifying what can and should be electrified directly is going to be important,” he states. “We need to identify the synergies that do and can exist between renewable electricity supply, electrification, and hydrogen. Too often the question is framed as what hydrogen deployment will require from the renewable sector in terms of electricity for production but hydrogen must also be seen as a potential additional route to market for stranded renewable assets and a route into different sectors of the market for electricity.”

In relation to a targeted strategy, Monaghan believes that learnings can be gleaned from other countries but with the context that Ireland is unique to the likes of Germany, where a heavy industry base exists, or the UK, which is targeting its oil and gas industry. However, despite the targeting of different demand sectors across different countries, a consistent theme is the targeting of transport and industry.

Of all the priorities in shaping a hydrogen strategy, Monaghan stresses the need for coherence and believes the question that must be posed is ‘how can a national hydrogen strategy send the right signals to all stakeholders, while maintaining coherent policy positions?’

“Green hydrogen encompasses a wide variety of stakeholders and so it reaches into multiple policy domains. If we develop hydrogen in a siloed manner, for example, to specifically target heat or transport, we will see that it is an expensive solution. It is when we use hydrogen in an integrated way that it becomes a viable route to decarbonisation.”

Monaghan concludes: “Green hydrogen has a potential role in the Irish energy system. The synergies are clear, and the industry is ready, but there are risks. We need to collectively assess where hydrogen fits in Ireland’s energy system and agree a coherent position.”

Rory Monaghan is a lecturer of energy systems engineering in the School of Engineering at the University of Galway (formerly NUI Galway). He is the leader of the Ryan Institute’s Energy Research Centre, a funded investigator in MaREI, the SFI Research Centre for Energy, Climate and Marine, and the Director of the University of Galway Energy Engineering Programme.