Energy storage and the grid

8th December 2020

Calor’s journey towards a low carbon future

8th December 2020Decarbonising Ireland: The energy challenge

John FitzGerald, Chair of the Climate Change Advisory Council, argues that the increased ambition to tackle climate change must be matched by implementation of new measures to drive decarbonisation.

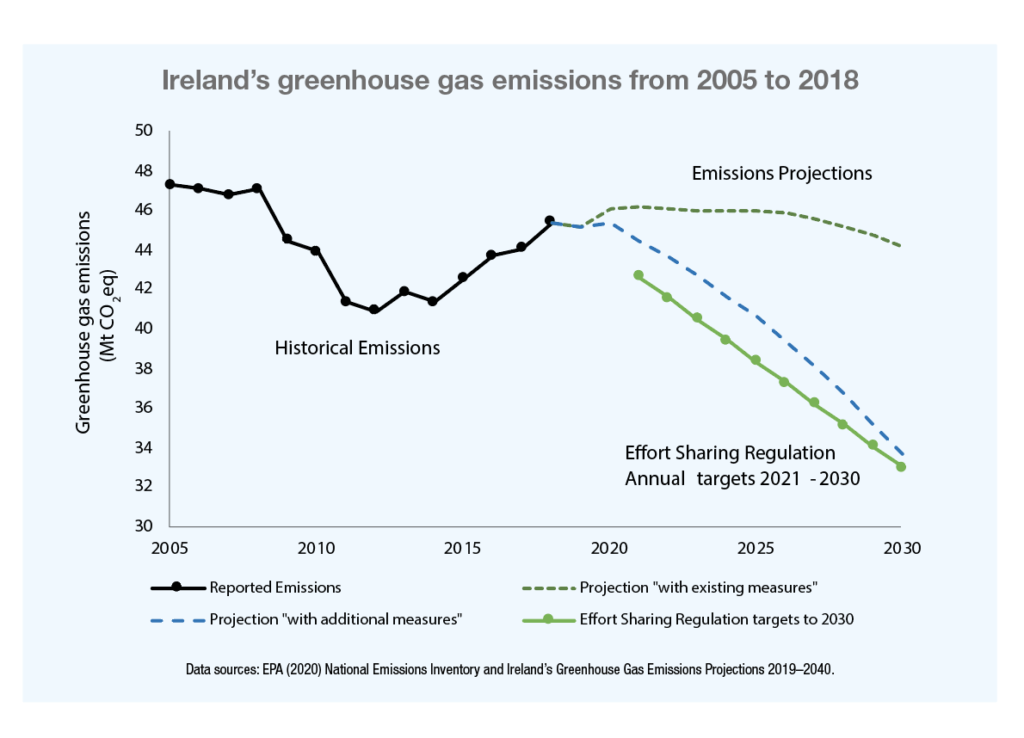

Outlining the failure to date to significantly reduce carbon emissions in Ireland, FitzGerald points to a coupling between the levels of national income and carbon dioxide emissions that has existed since the 1960s. The year 2000 marked a period of decoupling in this regard but by 2013 the economic recovery marked a rise in emissions once more.

FitzGerald points to data for 2018 which shows that the total emissions of greenhouse gases remained largely unchanged from 2017, but explains that the absence of a significant rise was largely driven by a 10 per cent reduction in the electricity sector due to reduced hours at Moneypoint power station, which masked significant increases in emissions in the residential, agriculture and transport sectors.

The analysis, says FitzGerald, is that not only have behaviours not changed significantly but that Ireland hasn’t even turned the corner in getting emissions to fall.

Outlining that Ireland will fail to meet the 20 per cent reduction of greenhouse gases target for 2020, despite an estimated 7 per cent reduction in emissions driven by the Covid-19 pandemic, FitzGerald points to a gap of between 12.6 to 13.4 Mt CO2eq on the Effort Sharing Decision (ESD) target of 337.9 Mt CO2eq.

“The reductions due to Covid-19 might bring that gap below 10 Mt CO2eq but we will still not meet our target and it’s important to remember that this reduction will be temporary. In this context, it’s important that investment to stimulate economic recovery must be ‘green’,” he states.

The Climate Action Plan 2019, if implemented fully, significantly changes the trajectory on emissions, explains FitzGerald but will still see Ireland fall short of the EU’s annual targets, meaning that Ireland will need to use the flexibilities allowed for on terms of land use. This, the Chair says, is more optimal than the other flexibility allowed for, the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which would allow Ireland to buy its way out of any gap to target but would not offer a long-term solution. “If we don’t meet even the current target for 2030 then we certainly won’t meet net zero carbon for 2050,” FitzGerald states.

The challenge of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Ireland comes in the face of increased ambitions both from the EU and within the new Programme for Government (PfG) for 2030.

FitzGerald admits that not all the additional measures in the new PfG have been fully analysed by the Climate Change Advisory Council but welcomes the “step up in ambition”, while also recognising the need for clarity on the new actions envisaged. “Additional action will be essential,” he argues.

The Chairman believes that the EU’s 2030 Climate Target Plan announced in September, which sets out an ambition of a 55 per cent greenhouse gas emission reduction across the EU by 2030 is a “potential game-changer” in terms of Ireland’s journey.

“The EU is upping their ambition and so we all have to up ours,” he says. FitzGerald believes that the likelihood that the EU are going to shift a lot of carbon dioxide emissions to the ETS would be helpful for Ireland and would change the policy challenge, however, he admits that how the EU policy will translate remains to be seen.

Setting out that the national position is still to see a reduction of 80 per cent of CO2 by 2050, FitzGerald says that the Climate Change Advisory Council support the proposed objective of the PfG to reach net zero emissions by 2050, but adds: “We need additional policy measures to the Climate Action Plan for a post-2030 world. The current planned policies are not enough to get us to that 2050 target.”

The Chair says that the first task must be to implement the measures of the Climate Action Plan. At the end of September, the Climate Change Advisory Council published its annual review, within which it cautioned that some of the measures within the Climate Action Plan may not work. “So, already there is a need for additional measures if we are to meet our existing 2030 target and of course, the new ambition will require further measures. We need to change behaviour in all sectors and not just rely on energy to do all of the work,” he adds.

Carbon tax

FitzGerald has long advocated for a steeper rise in the carbon tax, highlighting that behavioural change will not occur until the profitability of change is recognised. The Climate Change Advisory Council recommended a €35 per tonne tax for Budget 2021 (Budget 2021 saw a rise in the carbon tax from €26 to €33.50 per tonne), rising to at least €100 per tonne by 2030.

However, the Chair believes that with the hindsight of the pandemic causing a reduction in fossil fuel prices, the need for a higher carbon tax has never been more pertinent.

“The lower fuel prices since the Budget 2020 mean that, even with the higher carbon tax, all of our energy is going to be substantially cheaper. The Department has already showed, when producing the Climate Action Plan, that low energy prices lead to much bigger emissions and so we have a much bigger hill to climb because of those low energy prices.”

Those opposed to the rise in carbon tax often cite the potential impact of those in fuel poverty but FitzGerald believes that a solution lies in using some of the revenue raised through the carbon tax to avoid regressive impacts on low-income households. The Chair points to research which suggests the use of one third of revenue from a carbon tax to compensate those on low incomes would not only insulate them against the problem but actually render them financially better off.

“Using the revenue to protect those on low incomes so that they don’t lose out as a result of an increased carbon tax is essential,” he states.

Electricity

Turning to the issues which he believes must be addressed by additional measures in key sectors, the Chair says that in terms of electricity, the Government needs to accelerate the closure of coal-fired generation and finally shut down peat-fired generation. To this end, the Climate Change Advisory Council has suggested the introduction of a carbon price floor to support renewable energy and phase out fossil fuels, however, FitzGerald believes that the new EU proposals may render this step unnecessary. “We need to it to be profitable to shut down coal and peat generation or at least make it costly to keep them open,” he adds.

The Chair recognises the potential in new opportunities, such as offshore wind development, which he says may be important not just for Ireland but for the rest of Europe. However, he believes that investment is needed in necessary infrastructure to support the goals on renewable electricity and the roll out of electrification of transport and heating. FitzGerald emphasises the need for the initial emphasis to be in non-urban areas, highlighting these as areas where emission savings would be greatest.

“The CRU in their price review need to ensure that the distribution network is upgraded so that you can roll out decarbonisation quicker in rural areas than in urban ones,” he says.

Other changes will also be required, he explains, pointing to the need for greater level of interconnection, work already underway on green hydrogen and adding, “technological solutions will help us on our way in electricity”.

Transport

Turning to transport, FitzGerald outlines that the sector is 20 per cent of Ireland’s total emissions and this is a figure that is increasing. The Climate Change Advisory Council has voiced concerns that the current target for EV take up is going to be difficult to achieve and FitzGerald says that given the estimated expense to government, taxation and subsidy will be required and that it’s important that changes to the tax system begin now to encourage people to buy electric cars. Again, the Chair emphasises that priority should be given to those areas of high usage, namely rural areas. “The infrastructure, including the electricity, needs to prioritise where big money will be saved in tackling areas of longer commutes,” he adds.

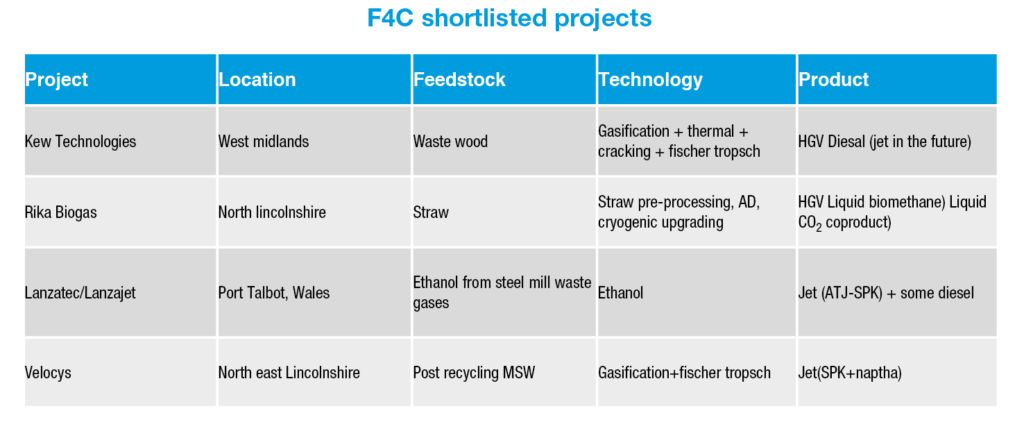

However, EVs alone will not offer a solution to the emission challenge in transport. “We need action on other forms of transport as well. The Climate Action Plan didn’t really deal with HGVs and LGVs but we need to look at these areas in case we don’t meet our target on EVs.” However, FitzGerald admits that the EV challenge may be aided by the new EU proposals which will likely see the EU’s car industry produce EVs “cheaper and earlier”.

Finally, on transport he calls the better planned development, citing the National Planning Framework as essential to facilitate public transport and active travel modes. “We’re set to build around another one million homes between now and 2050 and we must ensure that we put them in the right place where people have access to active travel modes. Investing in public transport is essential and BusConnects is a start but there is a need for further investment. The benefits of investment today will come in reduced emissions after 2030 but if we don’t do it now because it won’t effect our 2030 figure, then we won’t meet the 2050 goal.”

Built environment

On the built environment, FitzGerald acknowledges that the major deep retrofit of homes by 2030 is a challenging ambition. Highlighting that the retrofit of around 40,000 homes requires the same level of resources as that to build 5,000-10,000 new dwellings, he recognises that competition will exist between the Government’s ambition to build more homes and the desire to retrofit existing properties.

The Chair suggests that as well as increasing the capability of the building and construction sector, retrofitting efforts should be targeted at areas of most benefit and where the greatest level of emissions can be reduced: vulnerable households and those homes currently heated by coal, peat or oil. However: “High rates of retrofit cannot be achieved without unlocking low-cost finance for households and SMEs,” he adds.

Additionally, highlighting work already underway in the Department, FitzGerald points to the benefits of aggregation and the efficient management of this. “Finding ways to do this efficiently, which makes it easier, will make a significant difference. Making it profitable alone will not suffice, it must be easy,” he states.

Concluding, FitzGerald restates his belief that increased ambition to tackle climate change must be matched by the implementation of new measures to drive decarbonisation. “I want to see the announcement of things happening on the ground,” he stresses.

“Integrating a just transition into climate policy can add depth and assure public support for action. If policies are seen to be unfair then they are going to be very difficult to implement. Ensuring fairness is going to be an important task for policy for the future.”