Re-imagining a new electricity system

25th November 2019

Electric vehicles: vital for future mobility?

25th November 2019Decarbonisation: Barriers to progress

Examining Ireland’s climate change approach, Chair of the Climate Change Advisory Council John FitzGerald says there is still a long way to go to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

FitzGerald says that the Climate Action Plan, the Oireachtas Committee on Climate Action’s report and government commitment to increase the carbon tax represents significant progress on the decarbonisation journey but stresses his belief that Ireland still has a long way to go.

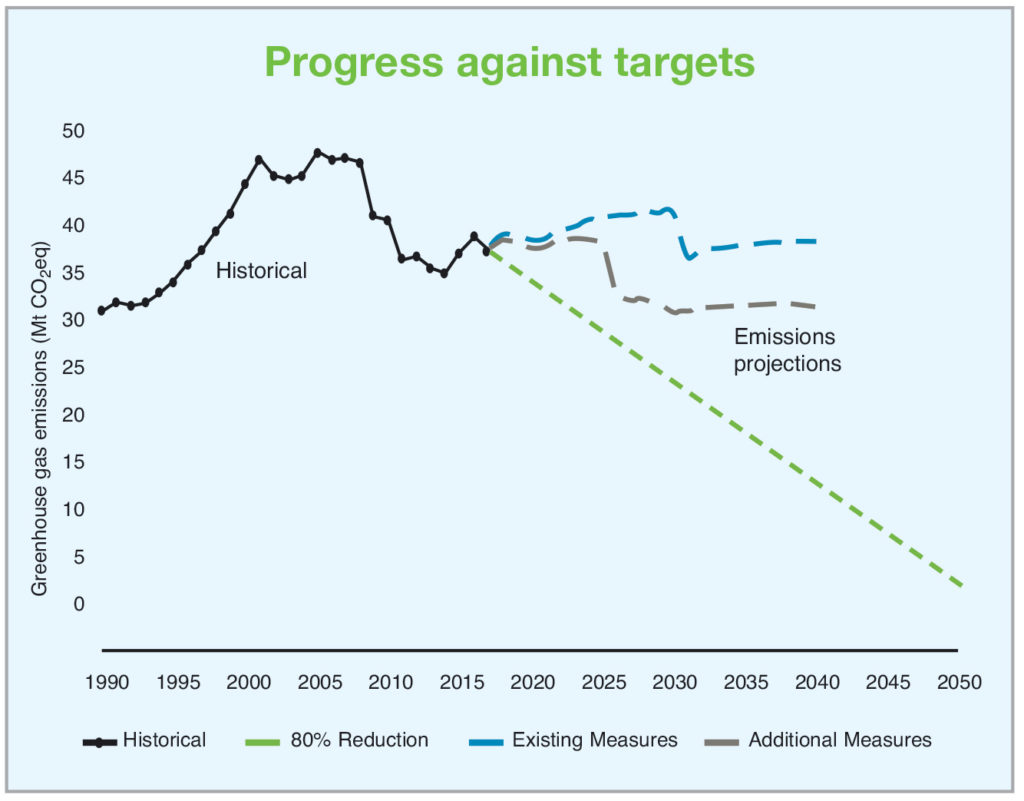

“We have improved governance and commitment, but we need to reverse the current trend in emissions which is still increasing, we need to reduce emissions by 40 per cent by 2030 and we need to be carbon neutral by 2050. All of these ambitions need policies and implementation,” he says.

Price

Since its establishment in 2015, the independent advisory body tasked with assessing and advising on how Ireland is making the transition by 2050, have stressed the importance of putting an appropriate price on carbon, to not only encourage the use of less energy but also to drive electrification.

“Electrification is being driven by the expectation that the price of using fossil fuels will go up. Unless we get the price right, that won’t happen. At a minimum the carbon tax would need to be €80 per tonne by 2030.”

FitzGerald was speaking just prior to the Government’s 2020 Budget which increased the carbon tax by €6 per tonne to €26 per tonne. The Council had called for a €15 per tonne increase and voiced their disappointment, however, it is recognised that applying a similar increase for the next decade would lead to reaching the level committed to in the all-party report on climate action.

“The fact that the vast number of parties in the Dáil accept the need for action on increasing the carbon tax is major progress. It means that future governments will likely have a commitment and understanding.”

FitzGerald and the Council have also voiced concerns that the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) price on carbon is too low, arguing for an appropriate ETS price. Finally, on price, FitzGerald queries the use of the Department’s assumed current price of carbon within the expenditure guidelines. Given their assumption of a price of €260 per tonne of carbon by 2050, this implies a price today of €80 a tonne. “If they are consistent in the plans when they publish them then every element of government investment should use a current price of €80 per tonne rising to €260. It means all investment by the State should take this into account.”

Distributional effects

Another aspect which FitzGerald believes needs greater attention is the distributional effects of investment in decarbonisation. “If we are going to get buy-in then it is essential that we take these into account. We need a focus on how we spend the revenue from the tax. If we are going to make progress then part of that progress will involve convincing the people of Ireland that the revenue will be used to help us decarbonise.”

FitzGerald states that consideration must also be given to the small number of workers within the peat industry and the communities surrounding that industry so that they will not be losers from change. “This is a small issue for us here in Ireland but in Europe, in Poland, for example, there will be little progress until the coal industry workers are assured they will not suffer,” he says.

FitzGerald adds: “Also to be considered is the international issue in terms of our responsibilities to a wider world and recognising that where we spend our money in research and innovation will likely impact on how the developing world decarbonises while still growing.”

Transport

Turning to transport, FitzGerald says a number of issues still need addressed if Ireland is to achieve its ambitions for the electrification of private cars. Will Ireland have the infrastructure to support 900,000 EVs and how do we pay for this is one element, another is how Ireland equips for a much faster turnover of the car stock than it is used to.

FitzGerald explains that getting the tax structure for electric vehicles right is also hugely important. Dismissing suggestions that a carbon tax would be bad for rural Ireland, he says: “This is not the case if the tax structure is appropriate. The tax on motor vehicles should reflect the damage done to the climate and it should reflect the damage done to society in terms of congestion and road maintenance.”

Recognising that electrification of the private car fleet could see the Government lose some €5 billion in revenue, FitzGerald advocates the introduction of congestion charges, which he says will bear more heavily on commuters in urban areas than those in rural Ireland.

HGVs, he admits, are a huge challenge for the decarbonisation agenda. While compressed natural gas is seen as a variable transitional arrangement to reduce emissions, “the long-term solution is not apparent in terms of technology”.

Another challenge lies in the aviation sector, where FitzGerald believes there has been no progress made and the sector is one that tends to be ignored. “Emissions from aviation continue to grow. It’s an international problem but zero tax on the pollution from aviation means that this trend is unlikely to change.”

Heat

Outlining that Ireland will be required to invest around €50 billion over the next 30 years to upgrade housing to ensure climate resilience, FitzGerald says that transition must be profitable for households, if heat technology to decarbonise is to be adopted. However, he believes this raises a problem as “the current price of emitting carbon is too low”.

He also flags the challenge of scarce resources, believing that Ireland must develop the capacity of its building construction sector. “Currently, we are unable to build enough houses. If we move immediately to upgrading the necessary number of dwellings every year then it is estimated that this would result in 2,000 to 5,000 less houses.” FitzGerald recommends that the State concentrates its resources initially on upgrading local authority dwellings, helping to protect those on low incomes and also building the capacity of the building sector to deliver the necessary retrofit programme for all dwellings.

Finally, on heating, the Chair points out his belief that given that 7 to 8 per cent of the world’s emissions come from cement, a switch to timber frame houses and apartments could prove more carbon efficient and even cheaper, if explored.

Agriculture and land use

A focus area of the Council’s summer 2019 report and responsible for 35 per cent of Ireland’s carbon emissions, FitzGerald believes that decarbonisation of the agri sector presents an opportunity to enhance and safeguard farm incomes.

While FitzGerald recognises the current menu of options being proposed will save farmers money and reduce emissions, he believes more needs to be done. “We have recommended a reduction in the number of Ireland’s cattle. At the moment farmers make nothing from beef and a hard Brexit would see them losing a huge amount. However, alternative land uses in the form of woodland, hedgerows or alternative crops could help farmers make money and adjust to changing global demands.

On concerns around the future of the peat industry, he says: “The ongoing drainage of peat for extraction and other land uses is unsustainable. Incentives to encourage the appropriate management of degraded peatlands are required. The social implications of actions should be addressed to ensure a just transition, ensuring farming and rural communities benefit.”

Adaptation

Ireland needs to prepare and invest in becoming more resilient to climate change, states FitzGerald. “Ireland has experienced several extreme weather events in recent years which have shown the vulnerabilities of our society and economy. However, investment in adaptation requires partnership between government and the private sector and much of the adaptation must be done by companies and households. Decisions being taken for the future must consider a range of global warming scenarios, including even higher warming than 2oC.

“Sectoral adaptation plans and local authority adaptation strategies will play a key role in increasing climate resilience. However, key areas, including our coasts, housing and building standards and planning are currently not being addressed. The Government must raise the profile of adaptation and incorporate it into coherent policy on investment.”

Concluding, FitzGerald summarises: “Ireland remains off course to address climate change and adaptation to the impacts of climate change continue to be essential. However, opportunities do exist, particularly in the agriculture and land use sectors but urgent action is required. Appropriate policies can simultaneously substantially reduce emissions and enhance farm incomes.

“To progress, the carbon tax must increase to provide the necessary signal to enable the transition. Integration of a just transition into climate policy can add depth and assure public support for action.”