Importance of communities in a distributed energy future

6th December 2020

Solar shines bright in RESS-1

8th December 2020Bioenergy: A role in heat and transport decarbonisation

Government support for an enhanced role for bioenergy in Ireland’s future energy mix has not been forthcoming with the major focus remaining on the electricity sector.

Significant progress in decarbonising Ireland’s electricity generation is being undermined by rising (pre-Covid-19) carbon emissions in the areas of heat and transport, with overall energy generation heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

Heat accounts for close to 40 per cent of final energy consumption in Ireland and makes up 35 per cent of all energy related emissions. A total of 94 per cent of energy for heat still comes from fossil fuels.

Bioenergy has been recognised globally as having a role in future energy security, removing the necessity for imported fossil fuels with carbon neutral domestic fuel. However, in Ireland bioenergy makes up just 4 per cent of Ireland’s energy mix.

Despite recognition of the Programme for Government’s outlook as the most climate ambitious of any government in the State’s history, the agreed outlook for the new tri-party coalition included just one line on bioenergy.

Under its mission of a Green New Deal, the Government said that far-reaching policy changes will be developed across every sector to deliver its expanded and deepened climate ambition and as a result they are “rapidly evaluating the potential role of sustainable bioenergy”.

This is in stark contrast to weight and support given to continuing the decarbonisation of the electricity sector through the promotion of solar and offshore wind generation. Undoubtedly, the Government recognise the opportunity presented by the future electrification of the heat and transport sectors if the electricity system can be fully decarbonised, however, this alone is unlikely to provide the levels of carbon reduction needed to meet 2030 targets in such a short period of time.

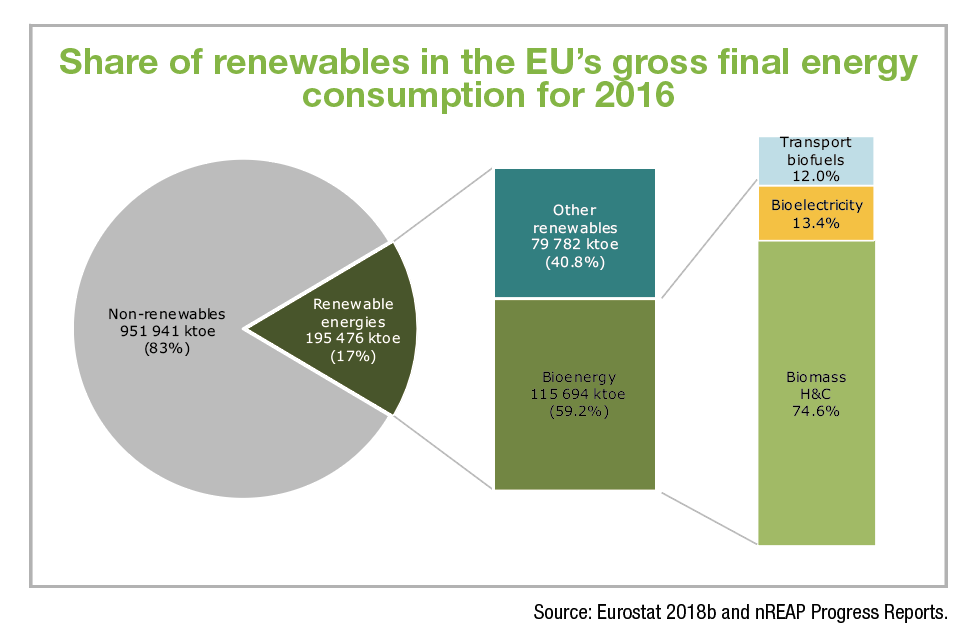

Bioenergy, the world’s largest source of renewable energy, provides an estimated 13 per cent of global energy supply, compared to the almost 5 per cent provided by other renewables combined. In the EU, bioenergy is the main source of renewable energy with a share of almost 60 per cent, Heating and cooling remains the largest user sector, taking around 75 per cent of all produced bioenergy.

According to the European Commission Germany, France, Italy, Sweden and the UK are the largest bioenergy consumers in absolute terms, while the Scandinavian and Baltic countries, as well as Austria, consume the most bioenergy per capita. Although Ireland has a perceived land and climate advantage in producing bioenergy, it ranks 27th of the 28 member states (UK included) in terms of its use of renewable heat.

Although Ireland has focussed on the decarbonisation of electricity, efforts in the area of heat have not been totally absent. In June 2019, then Minister for Communications, Climate Action and Environment, Richard Bruton TD opened the second phase of the Support Scheme for Renewable Heat (SSRH), which provides operational support for biomass boilers and anaerobic digestion heating systems.

Biomass

However, any moves to deliver bioenergy production at scale have so far been delayed in Ireland. One reason for this may be the challenges that surround mass production of bioenergy. Although the benefits of a neutral carbon cycle created by the production of energy from biofuel are recognised, so too is the fact that careless use of biomass has potential negative impacts on climate change.

The three main areas of concern are:

• The risk of supply chain emissions in creating biomass for energy generation;

• The use of mature trees and replacement by younger trees causing a short-term carbon debt; and

• The cultivating of energy crops causing land use change which reverse carbon emission savings.

The EU’s 2021 Renewable Energy Directive attempted to address some of these concerns and implement regulation on the bioenergy sector. The Directive made a requirement for proof of suitable land and forest management to reduce the risk of harmful land-use change carbon debt.

The Directive ruled that biomass fuels could not come from protected and highly biodiverse and that forest biofuels could not come from areas of conservation. Also, that the productivity capacity of forests must not be reduced and that any sourcing from forests must minimise the impact of soil quality and biodiversity.

In May 2020 the European Commission announced its policy strategy aimed at recovering biodiversity by 2030. The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 is set out as a “comprehensive, ambitious, long-term plan for protecting nature and reversing the degradation of ecosystems”. While the Strategy did not include any legal proposals in relation to bioenergy, its recognised that the strategy could be worked into reviews of legislation affecting biofuels and biomass.

The commission is assessing, until the end of 2020, EU and global biomass supply, demand and sustainability. The assessment will feed into the commission’s review and revision of renewables targets, the emissions trading scheme, and the EU’s regulation on land use, land use change and forestry “where necessary” in 2021.

|

EU biomass fuel sustainability criteria • Biomass fuels from energy crops must not come from protected and highly biodiverse land. • Biomass fuels from forests must not come from areas of conservation. • Biomass fuels must not reduce the long-term production capacity of the forest. • The sourcing of biomass fuels from forests must minimise the impact of soil quality and biodiversity. • You must be able to prove that biomass wood was legally harvested. |

The commission will also review data on biofuels with high indirect land-use change risk (ILUC) in 2021. The review aims to ensure EU laws on bioenergy are in line with the European Green Deal’s increased ambition, notably its target of a 50 per cent reduction in EU emission reductions by 2030 from 1990 levels, up from 40 per cent previously.

Analysis suggests that Ireland could meet up to 20 per cent of its current energy demand from domestic bioenergy demand by 2030, however, strict regulation and policy would be required to not only give confidence to the industry but also ensure that bioenergy is produced in a sustainable manner.

The decarbonisation of heat will be a much more difficult challenge than that of electricity and while a decarbonised electricity system will have a role to play in the future decarbonisation of heat through technologies such as heat pumps and district heating schemes, electrification alone will not achieve current targets in a timely manner.

To this end, bioenergy, with its ability to replace fossil fuels, create jobs and aide with rural regeneration will be under greater consideration from Government.

Biogas

While biomass, specifically the burning of wood for fuel, is the most prominent use of bioenergy globally, biomethane (biogas) is a recognised clean, renewable and carbon neutral fuel with potential to be used in heat, electricity and transport.

Ireland has the highest potential for renewable gas production per capita in Europe with 13 TWh achievable by 2030, the EU commission found, based on its large agricultural sector.

Biomethane generation and production is done through the upgrading of biogas, which is produced through anaerobic digestion of organic materials. The renewable gas can be used as a direct substitute for natural gas. Much of the focus of decarbonising the existing gas network is on the potential of hydrogen. Hydrogen will undoubtedly play a major role in decarbonising heat in Ireland out to 2050 and beyond but is still considered fairly immature in its development. While a range of pilot projects utilising hydrogen as a fuel are in operation, the prospect of it being utilised on the gas grid still remains some way off.

In June 2020, a major step was taken when biomethane was injected into the Irish gas grid for the first time at the injection point at Cush, County Kildare.

The complexity of decarbonising heat means that a range, rather than a single solution will be required if 2030 and 2050 targets are to be reached and to this end the bioenergy industry continues to lobby government for supports and policy to help mobilise the industry and realise its full potential.

The same argument can be made for the transport sector in that a range of fuels will be needed to play a part in decarbonisation. While greater uptake of EVs represents a huge opportunity for decarbonisation through electrification, there is also recognition that electrification may not offer a solution to some transport types, such as heavy goods vehicles. Some biomethane fuelled vehicles already exist in Ireland.

In Summary, bioenergy represents a significant opportunity for Ireland to diversify its energy mix. However, the role of bioenergy in that energy mix will depend on government policy and what levels of support the government intend offer to the industry. Given Ireland’s natural resources of wind and sun, it’s unlikely that bioenergy will play more than a contributing role to the decarbonisation of electricity. However, the advancement of the technology in Ireland and the recognition off deployment more widely, would suggest that it has a significant role to play in the decarbonisation of the heat and transport sectors.

In comparison: Scotland

Like Ireland, Scotland’s bioenergy in Scotland contributes around 4 per cent of final energy demand. In 2017, the Scottish Energy Strategy included the development of a bioenergy action plan as part of its ambition for 50 per cent of all energy consumed to come from renewables. In continuing to develop an action plan the Scottish Government commissioned research to more fully understand the scope for bioenergy in Scotland. The research findings included:

• Increasing the contribution that bioenergy makes by 2030 would require additional bioenergy plant to be built and deployed within the next decade;

• Based on typical capital, operating and feedstock costs, all of the bioenergy conversion technologies considered produce energy or fuel at a price that is higher than that produced by conventional technologies, based on current fossil fuel prices;

• Estimates of domestic bioresources suggest that several additional anaerobic digestion plant are technically feasible, but utilising the resource fully is likely to require the use of a mixture of feedstocks in some plant;

• Advanced conversion technologies such as gasification for power or to produce synthetic natural gas and advanced biofuels production could be commercially proven by 2030;

• Allowing for competing uses of some bioresources in other sectors of the economy, there is another 5.3 TWh per year (of primary energy), that is currently not collected or is disposed of as waste, that could potentially be utilised for bioenergy; and

• By 2030, further bioresources equivalent to 2 TWh per year (of primary energy) could be available.