District heating in Ireland

6th October 2023

Bringing communities on our journey towards a world fully powered by renewable energy

9th October 2023Meeting the Global Methane Pledge through biogas

Charlotte Morton, Chief Executive of the World Biogas Association (WBA), talks about the need for a global standardised approach in order to meet the objectives of the Global Methane Pledge.

Established in 2016 during the COP22 Climate Summit in Marrakech, Morocco, the World Biogas Association was initially founded by three national organisation members and 20 company members. The group now represents 100 organisations from all inhabited continents and is in leadership groups on the Climate and Clean Energy Hubs for Global Policy.

Morton cites a study by the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) which states that methane is 86 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide in its first 20 years in the atmosphere. “The Global Methane Assessment carried out by the CCAC demonstrates that tackling methane is the single most cost-effective way to keep temperatures below 2oC,” she says.

The Global Methane Pledge

Under the Global Methane Pledge, countries are committed to reducing methane emissions by 30 per cent against 2020 levels by 2030. More than 150 countries around the world are signed up to the pledge, including all European Union member states and the United States of America.

“Today, we are only recycling around 2 per cent of our organic wastes, so that shows there is a real opportunity to do something about this and we can do this if we put our minds to it,” Morton says.

“If we deliver all of the potential of reducing emissions from organic waste, that would deliver around half of the Global Methane Pledge. That alone could deliver over 0.1oC of a reduction in temperature.”

“One third of all food produced is wasted, 80 per cent of wastewater is returned to the environment untreated, and of the 33 billion tonnes of livestock manure and slurry, almost all is spread back to land untreated while crop residues are often burnt causing an air quality issue.

“Mismanagement of these organic wastes is responsible for 6 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, contaminating freshwater and spreading disease and reducing biodiversity. This makes you realise how significant the contamination of our water streams and the sea is.”

Uses of organic waste

Outlining the need to reduce organic waste and recycling them as much as possible, Morton states: “Anaerobic digestion is the technology today which gets the most value out of these wastes which is why, as an organisation, we promote the use of anaerobic digestion as the core technology. There are also lots of other complementary technologies which add value too.

“Collectively, if we could halve food waste – which is generally accepted that it would deliver 3 per cent reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions – and recycle all organic material which would reduce methane by 6 per cent, and displacing the fossil products with biomethane and digestate which would deliver a further 5 per cent, we would deliver a total greenhouse gas emissions saving of around 14 per cent.

“This is a really big number and there are lots of other benefits to that as well, not least contributing to nine United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Moreover, all of that organic material contains the equivalent of around one-third of today’s global gas demand, there is a lot of valuable energy in there.”

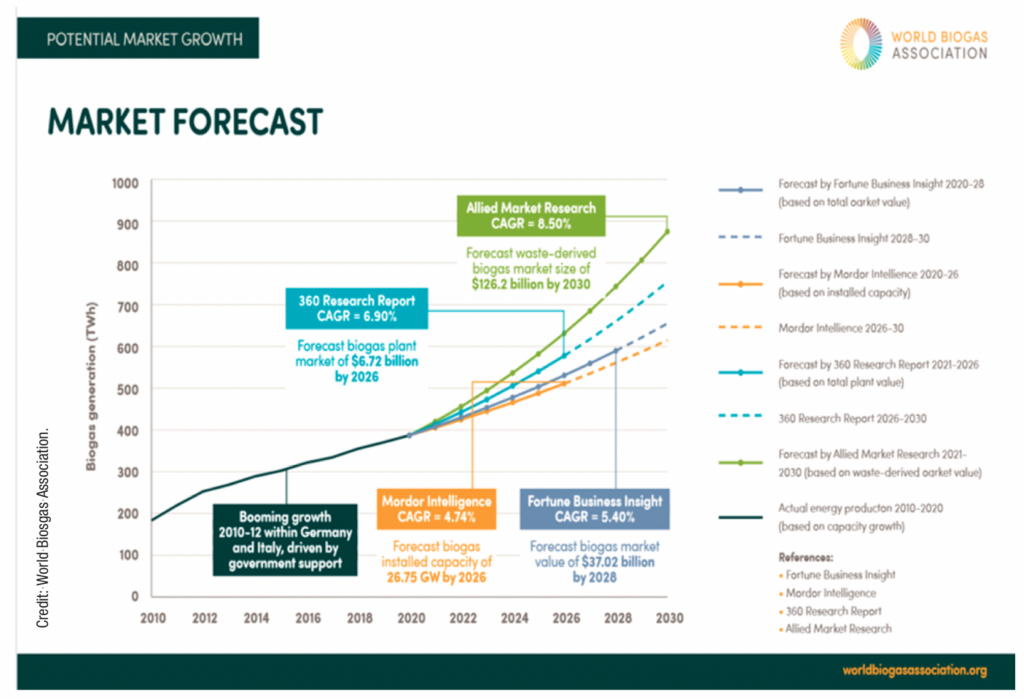

Growing the biogas industry

Describing projections for growth of the biogas and biomethane sectors as “exciting”, Morton says: “The International Energy Agency [IEA]’s forecasts show that this industry is the second fastest growing energy sector in the planet.

“The global north is absolutely in a position to implement the kinds of policies that would allow biogas plants to be delivered at scale and fast. The global south would take a bit longer because in many parts of the global south there is not yet waste collection infrastructure in place, so it will take some time to put that in place first before the organics can be recycled.”

She further outlines how anaerobic digestion can also be a carbon-negative technology. “There are some companies which are focused already on building plants with a view to capturing the CO2, liquefying it, and putting it in the ground.”

Concluding, Morton emphasises the importance of a streamlined planning process, as upscaling global anaerobic digestion infrastructure will require construction of digestors at an unprecedented rate. “In the UK, it takes around seven years to get a permit for one plant. Given that we need to make hundreds of thousands of plants globally, we need to radically change the way in which planning and permitting happens.”