Imagining a better way: Bord Gáis Energy’s Teresa Purtill

3rd January 2023

The potential impact of the disruption in Russian gas supplies to Europe

3rd January 2023Irish energy poverty reaches highest recorded rate

Irish energy poverty has reached its highest recorded rate amid energy price inflation, with the estimated share of households experiencing energy poverty now standing at 29 per cent.

Operating under the definition of energy poverty as a household spending more than one-tenth of its net income on energy (including electricity but excluding motor fuel), an ESRI report published in June 2022 found that an estimated 29 per cent of households in the Republic now qualify as experiencing energy poverty. The previously recorded high for this stat was 23 per cent, recorded in 1994/95.

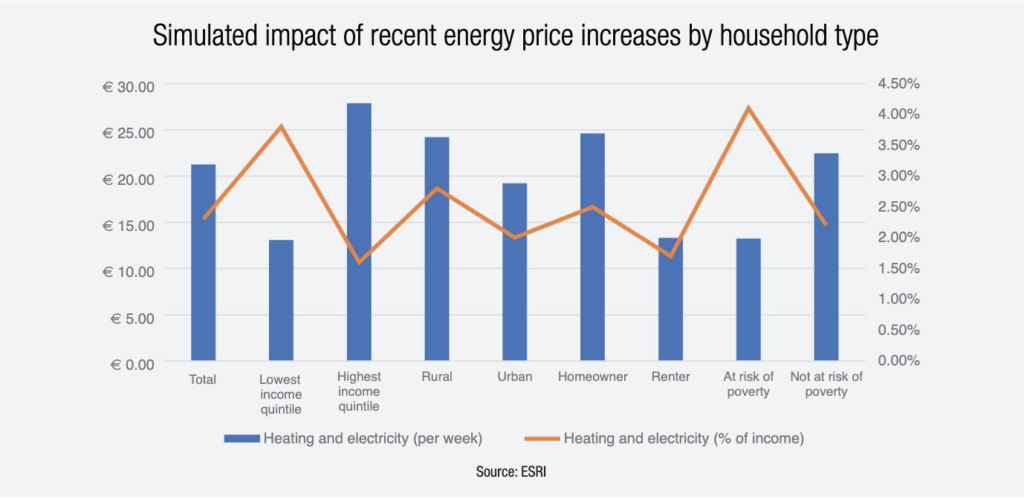

This estimate was arrived at via observation of energy inflation from January 2021 to April 2022, a period in which household consumption costs increased by €21.27 per week on average, rising to €38.63 per week when motor fuels are included; these figures equate to 2.3 per cent and 4.2 per cent of disposable income across all households respectively. The ESRI estimates that a further 25 per cent rise in energy prices would result in the share of households in energy poverty rising to 43 per cent.

The figures bring into stark focus the recent and extreme nature in the inflation of energy prices; as noted in the Oireachtas Library and Research Service’s March 2022 report Energy Poverty in Ireland. The ESRI itself had estimated the share of households in household poverty to be 17.5 per cent in 2020, while the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications estimated 28 per cent of households to be “in or at risk” of energy poverty in 2016, and the Survey on Income and Living Conditions reported that 4.9 per cent of people were unable to afford to adequately warm their homes in 2019.

The ESRI research found there to be a “strong income gradient in the impact of energy price increases”, with it estimated that recent increases in energy costs, including motor fuels, amount to 5.9 per cent of after-tax and transfer income for households in the lowest 20 per cent of income, while it accounts for 3.1 per cent of the same income for households in the highest 20 per cent. This is deemed to be “because a larger share of lower-income households’ spending is on energy, particularly home heating and electricity”.

Energy Poverty in Ireland states: “It is well established that certain groups are more vulnerable to energy poverty and its consequences. This may be because they are poorer and have limited capacity to meet their energy costs, particularly in a fluctuating market reliant on imported fuels, or because they have increased energy needs, or both of these factors combined. Groups that are most frequently identified as vulnerable are low-income households (particularly larger households), lone parents, older people, children, and people with disabilities.”

The ESRI report, Energy poverty and deprivation in Ireland, also found the cutting of taxes such as fuel tax, VAT, and carbon tax to be a “poorly targeted response” if the aim is “to protect those most affected by rising energy prices”. This conclusion was reached due to the ESRI’s research showing that roughly half of the aggregate gain from such tax cuts go to top two quintiles of income, with less than one-third of the gain to the bottom two income quintiles.

Increases to welfare payments, the fuel allowance, and “even lump-sum payments like the household electricity credit” are instead cited as better targeted mechanisms to target those suffering from energy poverty according to the ESRI, which gives the example of a “Christmas Bonus-style double welfare payment” that “would result in gains that are larger in both cash terms and as percentage of income for lower- than for higher-income households, while avoiding blunting the incentive to invest in energy-saving technology”.

The Oireachtas Library and Research Service report notes that there are three broad approaches to combatting energy poverty: reducing demand for energy by improving efficiency through measures such as retrofitting; income supports in the form of transfer payments and subsidisation of bills such as the lump-sum recommended by the ESRI; and price regulation to control energy costs. As the report notes, various European directives contained within the 2019 Clean Energy for all Europeans package placed requirements upon member states to clearly define energy poverty, establish long-term renovation strategies for national stock, focus a share of their energy efficiencies measures on energy poverty, and to have “due regard” for energy poverty in their national energy and climate plans.

Domestically, the Climate Action Plan 2021 includes within it a pledge to tackle energy poverty via the ringfencing of revenue to refund national retrofitting with an emphasis on low-income households. Under the National Development Plan, exchequer funding for retrofitting is expected to reach €2 billion by 2030. The plan also restates a commitment to review the 2016-2019 Strategy to Combat Energy Poverty ahead of the publication of a new study, and to publish the findings of the Warmth and Wellbeing Study.

In 2020, the Fuel Allowance was paid to 22 per cent of households and 27 per cent received either the electricity or gas allowances provided under the Household Benefits Package, with exchequer expenditure in both reaching €290.45 million and €193.33 million respectively for the year. In 2022, payments under the Fuel Allowance total €33 per week for 28 weeks or two lump-sum payments, and payments under the Household Benefits Package total €35 per month in the form of credit to a utility bill or a cash payment. Assuming a four-week month, a recipient of both of these programmes would receive €167 per month, just about accounting for the €154.42 monthly increases (including motor fuel) incurred via the inflation from January 2021 to April 2022, leaving just over €12 in allowances to pay towards the rest of the costs.

As the Oireachtas report notes, liberalisation in the energy markets under EU rules mean that “price regulation is no longer a consumer protection measure since suppliers compete on price and set their own prices accordingly”; in studying the figures provided by both the ESRI and the Oireachtas Library and Research Service, it is clear that either this is a policy that will need to be revisited or the amounts paid out through schemes such as the Fuel Allowance will need to be vastly increased.