Energy storage for a sustainable future

12th November 2018

District Heating in Ireland: A real opportunity to decarbonise the heating sector

12th November 2018The future of the EU Emissions Trading System

Milan Elkerbout, research fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies’ (CEPS) Energy Climate House discusses the impact of the revision for the 4th trading phase of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS).

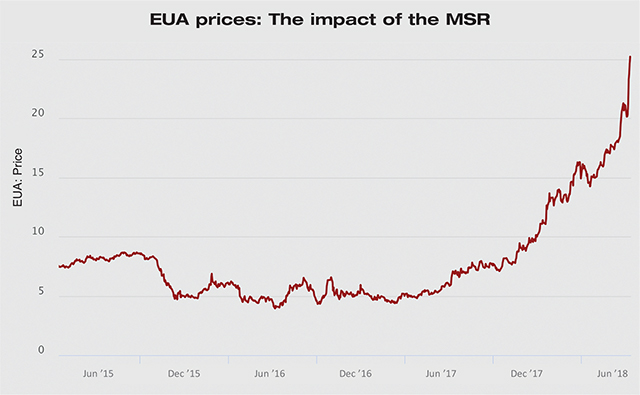

Setting the context of the EU ETS revision following the deal struck last November, Elkerbout highlights that European Union Allowance (EUA) prices are now five times above the levels of last year’s lows. This, he outlines, is on the back of over five years of continuous reform and reflects the anticipation of the beginning of the Market Stability Reserve (MSR), expected to add a degree of flexibility to the supply whilst making the system better equipped to deal with fluctuations in demand.

He also points to a rise in ETS emissions as a consequence of economic growth in industry over the last few years, following on from the early years of the system set during the economic crisis, when industrial emissions dropped precipitously along with growth levels.

The trend of phase three, the current trading phase to 2020, has seen a strong reduction in power sector emissions but these reductions have been offset in general by industrial emission stagnation. “The trend has been visible for the last three to four years and undoes a lot of progress achieved by the power sector,” says Elkerbout.

Addressing the revision’s impact on prices, he highlights that initially the market was unimpressed when the proposal was announced but this changed once the deal was completed last year, leading to a “spectacular performance”.

Phase 4

Outlining the key elements of the phase 4 revision, Elkerbout believes that the most critical is that of the MSR, which he describes as “an institutionalised means of backloading”, taking allowances from the auctions schedule and reintroducing them at a later stage.

“Another thing that can now happen from 2021 onwards is the choice or possibility of invalidation of allowances. If they sit there too long then they can get invalidated, at least to the extent that they exceed the previous year’s auction volume. Over time this could amount to some three billion allowances, which is about two years of emissions, which is not insignificant.”

Elkerbout states that there is also now a choice for member states to cancel extra allowances, if electricity generation is retired, while more generally there is a new strategic option to generate extra surplus, that could be invalidated later by the MSR by forcing extra domestic abatement.

The research fellow outlines that this has, at least temporarily, addressed the waterbed effect which was the concern of member states previously, whereby extra abatement by member states is unlikely to have an incentive under the single cap of the EU system. “The MSR does address this to some extent, but, because of the specific rules of the system, the impact is much more pronounced in terms of alleviating this waterbed effect for the first five years, rather than towards the end of the 2020s.”

Policy impact of price rise

Elkerbout highlights existing criticism that, even though EUA prices are now at €20-25, they are still not at fuel-switching levels. However, he believes that a price signal can be important at any level. He also highlights some member states advocating for an emergency break, embedded in the ETS directive, which allows for the convening of a committee if there is a too rapid increase in the price. Although, while the European Commission can be compelled to convene the committee, it has complete discretion on its final decision. “Actually, the EC is quite happy with what has happened here because it was a point of the reform to get carbon prices higher, even if this can’t be stated directly in Brussels,” he states, which instead prefers to refer to addressing supply-demand imbalances.

The impact of the revision has been that a lot of utilities in continental Europe are “hedging considerably”, although these patterns are changing. In the rest of Europe, the ETS is also important in terms of energy intensive industries, in particular steel, cement, refineries, and chemicals production. The most recently available data from April this year shows that the electricity sector is still the largest, although its share has been shrinking over time, especially in those countries who continue to focus extra domestic efforts on electricity sector emissions and closing coal-fired plants. However, the general trend is that with economic growth there has been a growth in emissions again.

Elkerbout draws attention to a change in free allocation rules, which has seen a shrinking of the share of free allowances for energy intensive sectors. In 2017, for the first time, at least some share of emissions in all sectors had direct exposure to the carbon price. There are now only three to four sectors that are responsible for the majority of free allowances and this has had a major impact on the system because free allocation surplus in recent years has contributed to depressing prices.

A look at the total UK ETS emissions, representing 3.9 per cent reduction compared to 2016, shows an enormous impact of the domestic carbon price floor in contrast to the rest of the EU.

Examining whether the revision has made the ETS a more credible and attractive system, Elkerbout says that looking long-term, under the rules agreed in November last year, the cap will reach zero in 2058. However, the EC’s and some member states’ adoption of ambitious national climate targets which are in excess of the EU target, makes it likely that this will be brought forward for revisions in the not-too-distant future.

“If electricity generation is retired, while more generally there is a new strategic option to generate extra surplus, that could be invalidated later by the MSR by forcing extra domestic abatement.”

“Another nice aspect is that treasuries will be delighted with the performance of the system in the last year. Revenues are going up, not just for treasuries but also for a vast number of funds for which a number of allowances have been ring-fenced, mostly for intensive industry but also a little bit for renewables. At current carbon prices, it will be over €1 billion a year that will be available.”

Outlook

Assessing the outlook for phase 4, Elkerbout states that due to new allocation rules, ETS will be a lot more capable to deal with any sort of fluctuations, even supply shocks caused by, say, a hard Brexit. “It doesn’t matter where a surplus will arise from, the system is more responsive to that. Having said that, there is still a hangover of surplus from earlier trading phases.”

He adds: “Most importantly, there is still an investment conundrum. There is a lot of low-carbon technology out there for industry but there is no market for it yet. For a market to exist, there would need to be far higher carbon prices and these carbon prices are not politically sustainable, so we need other policies to get that technology into the market.”

Brexit

Outlining the view from Brussels, Elkerbout says a genuine desire to continue co-operation on climate and energy exists. However, he explains that it will be subject to the general framework of co-operation.

“The most important element will be the role of the European Court of Justice and for the ETS, this is not something that can be wished away. Many times a year the court has rulings on how the ETS operated and in extremely detailed level with regard to allocation rules. It will not be possible to not have the court, or at least its case law, involved if the UK continue to participate in the ETS.”

Assessing that financial contributions of the UK will also be a factor on the post-Brexit operation, he adds: “Brussels really cares about process. While the withdrawal part has been advancing well now on this issue, it is completely separate from the future relationship, which will be negotiated separately.”

Outlining the existing association agreement, commonly known as the Ukraine model, which allows for varying degrees of co-operation on the environment, climate and energy legislation, he concludes that association agreements have proven in the past to be flexible instruments, however, all have been designed to slowly integrate countries into the EU, rather than to leave it, as the UK are seeking to do.